an illustrated story

Darwin Bushman. Astoria Greenly. Mavericks Yahoo.

This story is a love triangle.

Kip Numbgrin bucked a trend. The trend of internet devastation. Self-hatred, lost thoughts and dead communication. I am the man they call Kip Numbgrin."Do you have everything you need? I mean, everything you came with?" I said to my daughter on Sunday before her mother was to pick her up, take her away for 13 days.

Mavericks Yahoo was my friend.

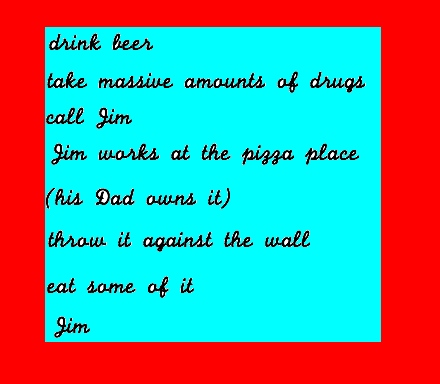

I met Mav in the army. We shot kangaroos in the outback. The kangaroos were half-robot and were real man-killing machines. They looked like this:

The War with Australia was a tough one.

My daughter's name is Sharon. Sharon's mom was late. She sat there with me in total silence, her backpack was colorful and strapped tightly to her body. My eyes fixed toward the window, the parking lot below, the door, I don't know. We waited. It felt painful, like getting shot by a laser and then hacked up with an axe and then eaten by a killer robot kangaroo. I seen it. Only I'm still alive. Is that worse? Knowing all that?

Let me commit suicide and be a ghost. Let the ghost narrate all the action. Action of lives. Seeing is believing. Seeing all is to believe in stories. Stories are all we got.

Mav lives across the hall. Our apartment building is called The Heritage. He met Astoria Greenly on the internet. Purple House, which was the thing after Facebook.

They lived on Purple House before meeting face to face. Astoria lived with a lot of guys on Purple House but only met Mav and Darwin in real life.

Years earlier, my ex-wife Sandy, who was still my wife at the time, we had my daughter's head removed in church. We didn't meet online. We opted for the head of a bright yellow dinosaur. So my daughter looks like this:

Such is life with a God like Ezo.

Darwin comes from different stock. He never had to join the army. I see Astoria look into his eyes and it's like she's using expensive mustard or something.

My wife's new husband is his brother, Barry Bushman. I see a bit of him. And occasionally them. It would hurt to tell Mavericks about these things that I know. I am drifting. Life is real.

My head is my own head. We only decapitate children.

I thought, "Sweet-talk the imperatives." A very vague thought about motivation, motivating myself to move, do something, anything. Swirling around inside my head. It felt like Sandy and Barry were never gonna get there. I have no TV or internet.

"This child will have to eat again soon. And I am out of animal carcass," I thought.

I heard Mavericks whistling outside the door down the hall. His typical whistle of optimism. I stepped out and he nodded at me. "Got any raw meat?" I asked.

"Sure," he said. "How's Sharon doing?"

"Not too bad. Her mom is late again."

"Oh."

I followed Mav into his apartment. There is a statue of a woman in there made out of coat hangers and green fabric. This is the woman modeled after Belle, Mav's lost Aussie love from the war.

"Praise Ezo it sure is hot out," exclaimed Mavs.

"Hey why did you make Belle here green?"

"I never told you that?"

"No."

"Well," Mav said as he settled on a temperature with the air conditioner's remote control, sat down and kicked off his boots. 68.8 °F. "Well."

"You know I think Sharon and Barry are going to have a newfangled litter of hybrid children. Sea beasts." I thought about baby sea beasts spliced with human child DNA. "Say, what about that meat for my daughter before I forget?" I asked.

"Sure, hamburger okay?"

"That's fine." I thought about Sandy and Barry Bushman's hypothetical litter of sea beast offspring as Mavericks Yahoo fetched raw ground beef out of the freezer for my daughter.

I thought,

The hamburger meat is all gone and my daughter is fine. She wouldn't have complained to begin with because she is a good girl. But I knew she was hungry. It is her dinosaur head. It needs to be fed raw meat almost constantly. I walk back across the hall into Maverick's apartment.

"Damn," he says. "They still not here?"

"No."

"Damn."

I scratch my face.

"Hey Kip, why did you start messing around behind Sherry in the first place? Was it the war?"

"No," I say. I don't want to think about this. "My dad died. Probably, you know, my childhood."

The place and time is:

My dad is dead and there’s no coming back for him. That’s what dead is. They thought it needed to be explained. I appreciated the talking though, the different sounds of their voices.

I’m in my room deciding which toys I am going to sell. My dad has no headstone on his grave because we couldn’t afford to buy him one. The idea for the yard sale was mine. It made my mom cry.

A few days ago, I said to my mom when she was half-crying on the bed, “Mom, you could sell some of your shoes.” I was in her closet and the pile of shoes looked huge. She bellowed and scratched at her arms like she wanted her fingernails to be knives. I imagined that they were knives and I saw many rivers of blood pour out of her.

When it happens in about 48 hours I will sail those rivers of blood for all eternity. There’ll be no coming back for me, not really.

For now, I am a child, 11 years old, alone in a room full of toys. I do not need these toys. I say to the yellow stuffed animal, “I do not need you, yellow stuffed animal.” The yellow stuffed animal is either a bird or a monster. Its spirit will join me on the rivers of blood when it happens.

How does it happen? It starts with a telephone call, which will seem funny later.

My mom likes shoes, and I think she should keep all her shoes. It was wrong of me to ask her to sell her shoes. She says my name on the telephone. I don’t know who she’s talking to. She talks about my yard sale like it is some kind of magical thing. It is not.

I will still have the yard sale after it happens. The yard sale will become part of it.

When it happens, time will stop. It happens. It is happening. People say, “email, Twitter and Facebook.” I know what all these things are. This is how it happens. I think the best place for the sign promoting my yard sale will be at the corner of my street and Grover Avenue, which isn’t too far away and gets a decent amount of traffic. The sign is a piece of white poster board and it’s just a simple sign. It says, “Yard Sale, 9AM-2PM, #14 Moore Ln.” I used a thick red marker, but no bubble letters. I hate the look of bubble letters.

The sign turns out to be unnecessary and I think I might have known that while I was making it.

There are many more people around, most of them strangers. I just want to have the yard sale and then leave, get on with it. I'm feel unsure about things.

Tom Cochrane shows up.

He is followed by a camera crew, or the camera crew is just there. I think I recognize some of them from yesterday.

My mom begins to sing a bit of “Life is a Highway.” She does not have a good voice. She sings, “Life is a highway. I want to ride it all night long.” She seems like a maniac and I am embarrassed. I now have the money to go to college anywhere in the world, anywhere I want. I am told this. Several people tell me this. I am 11 years old. My father is dead.

Someone, possibly an aunt or one of my mother's friends, says that it would be a good idea if I donated the extra yard sale money to charity. I don’t care. I just want it to be over, I think. I say, "Yes, sure. Charity can have this money." Tom Cochrane signs an electric guitar with a Sharpie. Someone photographs us shaking hands. Someone puts the guitar with Tom Cochrane's signature on the fold-out table next to some of my stuffed animals. I see the yellow monster. Or is it a bird? Its spirit talks to me for the very first time. “Soon,” it says. Most of this stuff is being sold online, I am told. Very little money is exchanging hands.

When things finally calm down, and the people with cameras and all the other people without cameras begin to leave, I am on the rivers of blood. I have been on them for a long time, years. I am drifting. I’m hardly missed. Maybe I have been here the whole time, maybe I am am still here. Navigating the rivers is like a full-time job. The spirit of the yellow stuffed animal is named Bob. He is the first mate on the boat on which we sail the rivers of blood. Before we departed, he set up a hidden camera over the world we used to know. We don’t get to watch the security monitors too often because the rivers of blood are tricky. Getting lost is a real problem. But when I do get to watch the tapes, I see a lot of the same.

The house looks the same. My mom is dating someone new. The college trust fund is living in the doghouse in the backyard. When I left, nobody wanted to care for the dog, my dog Bo. So Bo wound up in a shelter and was put to sleep 3 weeks later. Bo is dead. I fear I’ll meet his ghost soon enough. The trust fund seems happy and is much easier to care for than a dog.

“Let’s get milkshakes,” Bob says. The milkshake store is 7 left turns, 2 rights, a circle thing and then a sideways climb up a part of the river that has a conveyor belt underneath it. Living on a boat on the rivers of blood is not unlike being on hard drugs at a waterpark. You have to get the boat going just the right speed to hit this particular lift correctly. If you don’t, you might flip right over the side. And the sides of these rivers are a black abyss. Our minds make the black abyss but the danger is real. We are basically going up a waterfall to get to this milkshake store.

But the milkshakes are worth it. “Best milkshakes around,” I say.

One of the biggest things Bob and I look for, when we have time to check the security monitors, are signs that I am gone. “You see there,” Bob says. “That look? She is sad that you are gone.”

“I think she’s just thinking about lunch,” I say. Bob somehow hooked up the security footage to play on his iPhone. He is excellent with technology. We order two milkshakes each. We stare at his phone while we wait for the milkshakes.

I can remember the face of the tombstone salesman vividly, his skin. He was from Texas. It was like elephant skin dipped in beige mud and then glued on to human facial skin with holes cut out for the eyes, nostrils and mouth. The color of my two milkshakes is not quite like the color of his skin. But I like thinking that something made me think of him, that I just didn’t start thinking of him on my own.

He came all the way to Canada to deliver the headstone personally. He shook my hand. His hand skin felt softer than his face skin looked. Even at a 11 years old, I knew that was impossible. I have no age on the rivers of blood, no use for skin either. The tombstone salesman talked to Tom Cochrane for about 15 minutes.

Bob and I get up on one of the tables at the milkshake store and do a little dance. The milkshakes look great swirling around inside our transparent bodies.

Where is Jim? Jim would know what to do.

I am taking mental notes, that’s all. That’s all I am. Mental notes aren’t musical. I’m no Tom Cochrane.